According to wikipedia, “Jean Philippe Arthur Dubuffet (July 31, 1901 – May 12, 1985) was one of the most famous French painters and sculptors of the second half of the 20th century.” “He coined the term Art Brut (meaning “raw art,” often times referred to as ‘outsider art’) for art produced by non-professionals working outside aesthetic norms, such as art by psychiatric patients, prisoners, and children.” From this interest, he amassed the Collection de l’Art Brut, a sizable collection of artwork, of which more than half, was painted by artists with schizophrenia. One such painting that typifies this style is shown here, entitled, General view of the island Neveranger (1911) by Adolf Wolfe, a psychiatric patient.

According to wikipedia, “Jean Philippe Arthur Dubuffet (July 31, 1901 – May 12, 1985) was one of the most famous French painters and sculptors of the second half of the 20th century.” “He coined the term Art Brut (meaning “raw art,” often times referred to as ‘outsider art’) for art produced by non-professionals working outside aesthetic norms, such as art by psychiatric patients, prisoners, and children.” From this interest, he amassed the Collection de l’Art Brut, a sizable collection of artwork, of which more than half, was painted by artists with schizophrenia. One such painting that typifies this style is shown here, entitled, General view of the island Neveranger (1911) by Adolf Wolfe, a psychiatric patient.

Obviously, Wolfe was a gifted artist, despite whatever psychiatric diagnosis was suggested at the time. Nevertheless, clinical psychiatrists might be quick to point out that such work reflects the presence of an underlying thought disorder (loss of abstraction ability, tangentiality, loose associations, derailment, thought blocking, overinclusive thinking, etc., etc.) – despite the undeniable aesthetic beauty in the work. As an ardent fan of such art, it made me wonder just how “well ordered” my own thoughts might be. Given to being rather forgetful and distractable, I suspect my thinking process is just sufficiently well ordered to perform the routine tasks of day-to-day living, but perhaps not a whole lot more so. Is this bad or good? Who knows.

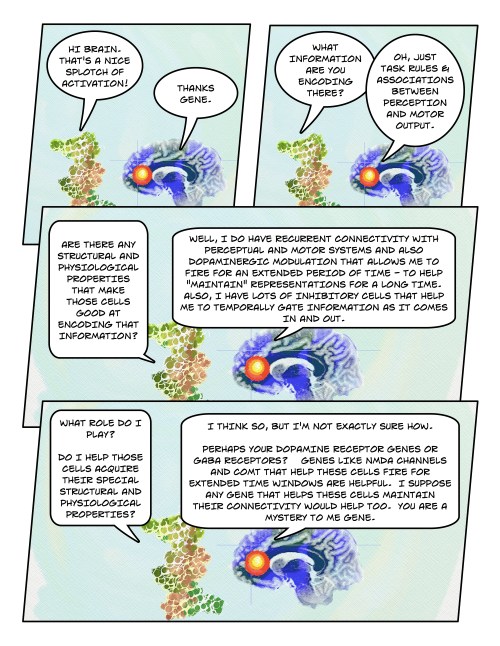

However, Krug et al., in their recent paper, “The effect of Neuregulin 1 on neural correlates of episodic memory encoding and retrieval” [doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.062] do note that the brains of unaffected relatives of persons with mental illness show subtle differences in various patterns of activation. It seems that when individuals are using their brains to encode information for memory storage, unaffected relatives show greater activation in areas of the frontal cortex compared to unrelated subjects. This so-called encoding process during episodic memory is very important for a healthy memory system and its dysfunction is correlated with thought disorders and other aspects of cognitive dysfunction. Krug et al., proceed to explore this encoding process further and ask if a well-known schizophrenia risk variant (rs35753505 C vs. T) in the neuregulin-1 gene might underlie this phenomenon. To do this, they asked 34 TT, 32 TC and 28 CC individuals to perform a memory (of faces) game whilst laying in an MRI scanner.

The team reports that there were indeed differences in brain activity during both the encoding (storage) and retrieval (recall) portions of the task – that were both correlated with genotype – and also in which the CC risk genotype was correlated with more (hyper-) activation. Some of the brain areas that were hyperactivated during encoding and associated with CC genotype were the left middle frontal gyrus (BA 9), the bilateral fusiform gyrus and the left middle occipital gyrus (BA 19). The left middle occipital gyrus showed gene associated-hyperactivation during recall. So it seems, that healthy individuals can carry risk for mental illness and that their brains may actually function slightly differently.

As an ardent fan of Art Brut, I confess I hoped I would carry the CC genotype, but alas, my 23andme profile shows a boring TT genotype. No wonder my artwork sucks. More on NRG1 here.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)