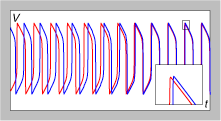

**PODCAST accompanies this post** In the brain, as in other aspects of life, timing is everything. On an intuitive level, its pretty clear, that, since neurons have to work together in widely distributed networks, they have a lot of incentive to talk to each other in a rhythmic, organized way. Think of a choir that sings together vs. a cacophony of kids in a cafeteria – which would you rather have as your brain? A technical way of saying this could be, “Clustered bursting oscillations, with in-phase synchrony within each cluster, have been proposed as a binding mechanism. According to this idea, neurons that encode a particular stimulus feature synchronize in the same cluster.” A less technical way of saying this was first uttered by Carla Shatz who said, “Neurons that fire together wire together” and “Neurons that fire apart wire apart“. So it seems, that the control over neural timing and synchronicity – the rushing “in” of Na+ ions and rushing “out” of K+ ions that occur during cycles of depolarization and repolarization of an action potential take only a few milliseconds – is something that neurons would have tight control over.

**PODCAST accompanies this post** In the brain, as in other aspects of life, timing is everything. On an intuitive level, its pretty clear, that, since neurons have to work together in widely distributed networks, they have a lot of incentive to talk to each other in a rhythmic, organized way. Think of a choir that sings together vs. a cacophony of kids in a cafeteria – which would you rather have as your brain? A technical way of saying this could be, “Clustered bursting oscillations, with in-phase synchrony within each cluster, have been proposed as a binding mechanism. According to this idea, neurons that encode a particular stimulus feature synchronize in the same cluster.” A less technical way of saying this was first uttered by Carla Shatz who said, “Neurons that fire together wire together” and “Neurons that fire apart wire apart“. So it seems, that the control over neural timing and synchronicity – the rushing “in” of Na+ ions and rushing “out” of K+ ions that occur during cycles of depolarization and repolarization of an action potential take only a few milliseconds – is something that neurons would have tight control over.

With this premise in mind, it is fascinating to ponder some recent findings reported by Huffaker et al. in their research article, “A primate-specific, brain isoform of KCNH2 affects cortical physiology, cognition, neuronal repolarization and risk of schizophrenia” [doi: 10.1038/nm.1962]. Here, the research team has identified a gene, KCNH2, that is both differentially expressed in brains of schizophrenia patients vs. healthy controls and that contains several SNP genetic variants (rs3800779, rs748693, rs1036145) that are associated with multiple different patient populations. Furthermore, the team finds that the risk-associated SNPs are associated with greater expression of an isoform of KCNH2 – a kind of special isoform – one that is expressed in humans and other primates, but not in rodents (they show a frame-shift nucleotide change that renders their ATG start codon out of frame and their copy non-expressed). Last I checked, primates and rodents shared a common ancestor many millenia ago. Very neat – since some have suggested that newer evolutionary innovations might still have some kinks that need to be worked out.

In any case, the research team shows that the 3 SNPs are associated with a variety of brain parameters such as hippocampal volume, hippocampal activity (declarative memory task) and activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). The main suggestion of how these variants in KCNH2 might lead to these brain changes and risk for schizophrenia comes from previous findings that mutations in this gene screw up the efflux of K+ ions during the repolarization phase of an action potential. In the heart (where KCNH2 is also expressed) this has been shown to lead to a form of “long QT syndrome“. Thus, the team explores this idea using primary neuronal cell cultures and confirms that greater expression of the primate isoform leads to non-adaptive, quickly deactivating, faster firing patterns, presumably due to the extra K+ channels.

The authors hint that fast & extended spiking is – in the context of human cognition – is thought to be a good thing since its needed to allow the binding of multiple input streams. However, in this case, the variants seem to have pushed the process to a non-adaptive extreme. Perhaps there is a seed of an interesting evolutionary story here, since the innovation (longer, extended firing in the DLPFC) that allows humans to ponder so many ideas at the same time, may have some legacy non-adaptive genetic variation still floating around in the human lineage. Just a speculative muse – but fun to consider in a blog post.

In any case, the team has substantiated a very plausible mechanism for how the genetic variants may give rise to the disorder. A scientific tour-de-force if there ever was one.

On a personal note, I checked my 23andMe profile and found that while rs3800779 and rs748693 were not assayed, rs1036145 was, and I – boringly – am a middling G/A heterozygote. In this article, the researchers find that the A/As showed smaller right-hippocampal grey matter volume, but the G/A were not different that the G/Gs. During a declarative memory task, the GGs showed little or no change in hippocampal activity while the AA and GA group showed changes – but only in the left hippocampus. In the N-back task (a working memory task), the AA’s showed more changes in brain activation in the right DLPFC compared to the GGs and GAs.

For further edification, here is a video showing the structure of the KCNH2-type K+ channel. Marvel at the tiny pore that allows red K+ ions to leak through during the repolarization phase of an action potential. **PODCAST accompanies this post**

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png)