a poem by Katherine West from originsg on Vimeo.

- Image via Wikipedia

Joseph LeDoux‘s book, “Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are” opens with his recounting of an incidental glance at a t-shirt, “I don’t know, so maybe I’m not” (a play on Descartes’ “cogito ergo sum“) that prompted him to explore how our brain encodes memory and how that leads to our sense of self. More vividly, Elizabeth Wurtzel, in “Prozac Nation” recounts, “Nothing in my life ever seemed to fade away or take its rightful place among the pantheon of experiences that constituted my eighteen years. It was all still with me, the storage space in my brain crammed with vivid memories, packed and piled like photographs and old dresses in my grandmother’s bureau. I wasn’t just the madwoman in the attic — I was the attic itself. The past was all over me, all under me, all inside me.” Both authors, like many others, have shared their personal reflections on the fact that – to put it far less eloquently than LeDoux and Wurtzl – “we” or “you” are encoded in your memories, which are “saved” in the form of synaptic connections that strengthen and weaken and morph through age and experience. Furthermore, such synaptic connections and the myriad biochemical machinery that constitute them, are forever modulated by mood, motivation and your pharmacological concoction du jour.

Well, given that my “self” or “who I think of as myself” or ” who I’m aware of at the moment writing this blog post” … you get the neuro-philosophical dilemma here … hangs ever so tenuously on the biochemical function of a bunch of tiny little proteins that make up my synaptic connections – perhaps I should get to know these little buggers a bit better.

OK, how about a gene known as kalirin – which is named after the multiple-handed Hindu goddess Kali whose name, coincidentally, means “force of time (kala)” and is today considered the goddess of time and change (whoa, very fitting for a memory gene huh?). The imaginative biochemists who dubbed kalirin recognized that the protein was multi-handed and able to interact with lots of other proteins. In biochemical terms, kalirin is known as a “guanine nucleotide exchange factor” – basically, just a helper protein who helps to activate someone known as a Rho GTPase (by helping to exchange the spent GDP for a new, energy-laden GTP) who can then use the GTP to induce changes in neuronal shape through effects on the actin cytoskeleton. Thus, kalirin, by performing its GDP-GTP exchange function, helps the actin cytoskeleton to grow. The video below, shows how the actin cytoskeleton grows and contracts – very dynamically – in dendrites that carry synaptic spines – whose connectivity is the very essence of “self”. Indeed, there is a lot of continuing action at the level of the synapse and its connection to other synapses, and kalirin is just one of many proteins that work in this dynamic, ever-changing biochemical reaction that makes up our synaptic connections.

In their paper”Kalirin regulates cortical spine morphogenesis and disease-related behavioral phenotypes” [doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904636106] Michael Cahill and colleagues put this biochemical model of kalirin to the test, by examining a mouse whose version of kalirin has been inactivated. Although the mice born with this inactivated form are able to live, eat and breed, they do have significantly less dense patterns of dendritic spines in layer V of the frontal cortex (not in the hippocampus however, even though kalirin is expressed there). Amazingly, the deficits in spine density could be rescued by subsequent over-expression of kalirin! Hmm, perhaps a kalirin medication in the future? Further behavior analyses revealed deficits in memory that are dependent on the frontal cortex (working memory) but not hippocampus (reference memory) which seems consistent with the synaptic spine density findings.

Lastly, the authors point out that human kalirin gene expression and variation has been associated with several neuro-psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, ADHD and Alzheimer’s Disease. All of these disorders are particularly cruel in the way they can deprive a person of their own self-perception, self-identity and dignity. It seems that kalirin is a goddess I plan on getting to know better. I hope she treats “me” well in the years to come.

Posted in Frontal cortex, Hippocampus, Kalirin, Rho GTPase | Tagged Alzheimer's disease, Biology, Dendritic spine, Elizabeth Wurtzel, Gene expression, Joseph E. LeDoux, Memory, Prozac Nation, Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are, synaptogenesis | Leave a Comment »

- Image by kodomut via Flickr

For humans, there are few sights more heart-wrenching than an orphaned child (or any orphaned vertebrate for that matter). Isolated, cold, unprotected, vulnerable – what could the cold, hard calculus of natural selection – “red in tooth and claw” – possibly have to offer these poor, vulnerable unfortunates?

So I wondered while reading, “Functional CRH variation increases stress-induced alcohol consumption in primates” [doi:10.1073/pnas.0902863106]. In this paper, the authors considered the role of a C-to-T change at position -248 in the promoter of the corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH or CRF) gene. Its biochemical role was examined using nuclear extracts from hypothalamic cells, to demonstrate that this C-to-T nucleotide change disrupts protein-DNA binding, and, using transcriptional reporter assays, that the T-allele showed higher levels of transcription after forskolin stimulation. Presumably, biochemical differences conferred by the T-allele can have a physiological role and alter the wider functionality of the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis (HPA axis), in which the CRH gene plays a critical role.

The authors ask whether primates (rhesus macaques) who differ in genotype (CC vs. CT) show any differences in physiological stress reactivity – as predicted by differences in the activity of the CRH promoter. As a stressor, the team used a form of brief separation stress and found that there were no differences in HPA function (assessed by ACTH and Cortisol levels) in animals who were reared by their mothers. However, when the stress paradigm was performed on animals who were reared without a mother (access to play with other age-matched macaques) there were significant differences in HPA function between the 2 genetic groups (T-alleles showing greater release of stress hormones). Further behavioral assessments found that the peer reared animals who carried the T-allele explored their environment less when socially separated as adults (again no C vs. T differences in maternally reared animals). In a separate assessment the T-carriers showed a preference for sweetened alcohol vs. sweetened water in ad lib consumption.

One way of summarizing these findings, could be to say that having no mother is a bad thing (more stress reactivity) and having the T-allele just makes it worse! Another way could be to say that the T-allele enhances the self-protection behaviors (less exploration could be advantageous in the wild?) that arise from being orphaned. Did mother nature (aka. natural selection) provide the macaque with a boost of self-preservation (in the form of a T-allele that enhances emotional/behavioral inhibition)? I’m not sure, but it will be fun to report on further explorations of this query. Click here for an interview with the corresponding author, Dr. Christina Barr.

—p.s.—

The authors touch on previous studies (here and here) that explored natural selection on this gene in primates and point out that humans and macaques both have 2 major haplotype clades (perhaps have been maintained in a yin-yang sort of fashion over the course of primate evolution) and that humans have a C-to-T change (rs28364015) which would correspond to position -201 in the macaque (position 68804715 on macaque chr. 8), which could be readily tested for similar functionality in humans. In any case, the T-allele is rare in macaques, so it may be the case that few orphaned macaques ever endure the full T-allele experience. In humans, the T-allele at rs28364015 seems more common.

Nevertheless, this is yet another – complicated – story of how genome variation is not destiny, but rather a potentiator or life experience – for better or worse. Related posts on genes and early development (MAOA-here), (DAT-here), (RGS2-here), or just click the “development tag“.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Biology, DNA, Gene, Genetics, Health, Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, Rhesus Macaque, Stress | Leave a Comment »

- Image by Dollar Bin via Flickr

pointer to: download Power Point presentation hosted on the HUGO website entitled, “From the human genome to human behaviour: how far have we travelled?” (both English and Russian text) – by Ian Craig and Nick Yankovsky, Education Council Human Genome Organisation.

Covers recent findings on MAOA and 5HTT several and others also covered here.

Congrats to Hsien on the new position!

Posted in 5HTT, MAOA | Tagged Mental disorder, schizophrenia, Twin | Leave a Comment »

Al Franken ably handles a “taxed enough already” crowd on healthcare debate topics … democratic process at its best … the frontrow presence of a 90 y.o. lady draws some focus on how young folks resent being saddled with future debt to pay for current payouts – no one seems to take note or care that she is there. Go Senator Al!

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged economics, Health insurance | Leave a Comment »

- Image via Wikipedia

pointer to: Tales of a Borderline is an exhibition of artwork by artists with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). This disorder affects a person’s emotions, causing emotional instability. The exhibition currently features the work of artists Tamar Whyte, Anita Kaiser-Petzenka, Karin Birner and Irene Apfalter and has been curated by Dr. Dagmar Weidinger.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Art | 1 Comment »

- Image via Wikipedia

pointers to: “Personalized Genetics: DTC Genetic Tests Are Hype” and “The World of Genetic Genealogy and DTC Genetic Testing Never Sleeps…”

Even though the data collection technology still outpaces the deeper understanding of the data, we’re learning more and more all the time.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Genetic testing, Personalized medicine | Leave a Comment »

- Image bywww.dld-conference.com

via CrunchBase

Very much enjoyed Jeff Jarvis’ recent book “What Would Google Do?” on the new, next economy. There, the old strategy of hoarding information for competitive gain, is supplanted by internet-based demand for openness, spontaneity and honesty among a long tail of interconnected, self-organizing individuals and small communities. Jarvis traverses all facets of the economic landscape and sees how this new ethos is on the rise. Indeed, a new social-political-economic era seems to be emerging.

I was inspired to focus on the spontaneous, entrepreneurial act of opening up and sharing my personal thoughts and dig deeper into the issues I care about. Thanks Professor Jarvis!

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Book Reviews, books | Leave a Comment »

- Image by wstera2 via Flickr

pointer to: Bloomberg Economics Radio – two top healthcare economics experts amicably discuss (.mp3) the current reform efforts – both agree the mendacity and outright lies are deeply poisoning the debate. The first main issue is the so-called “uninsured issue” which most other countries have resolved (simply, everyone deserves to be and is covered) which they see as resolvable through public-private and/or private-exchanges for the 20-25 million folks who cannot afford coverage – at little or no extra cost to the tax payer. The much larger ($trillions$) question remains how to keep up with good medical care and keep down costs. Both agree that incentives to physicians that promote the use of evidence-based practices – rather than fee-for-procedure would accomplish this. However, both see this as a VERY long-term debate that will progress incrementally in the decades to come. Certainly the health 2.0 movement will transform this conversation in the decades to come.

A welcome respite of scholarship and collegial respect amidst the rising demagoguery in the heartland. Related posts here and here.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged economics, Health 2.0, Health insurance | Leave a Comment »

- Image via Wikipedia

pointer to: “Placebos Are Getting More Effective. Drugmakers Are Desperate to Know Why.” with details on the difficulties in developing meds to treat mental illness. One choice quote, “Ironically, Big Pharma’s attempt to dominate the central nervous system has ended up revealing how powerful the brain really is.”

A post related to genetics of placebo response here.

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

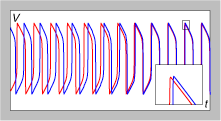

**PODCAST accompanies this post** In the brain, as in other aspects of life, timing is everything. On an intuitive level, its pretty clear, that, since neurons have to work together in widely distributed networks, they have a lot of incentive to talk to each other in a rhythmic, organized way. Think of a choir that sings together vs. a cacophony of kids in a cafeteria – which would you rather have as your brain? A technical way of saying this could be, “Clustered bursting oscillations, with in-phase synchrony within each cluster, have been proposed as a binding mechanism. According to this idea, neurons that encode a particular stimulus feature synchronize in the same cluster.” A less technical way of saying this was first uttered by Carla Shatz who said, “Neurons that fire together wire together” and “Neurons that fire apart wire apart“. So it seems, that the control over neural timing and synchronicity – the rushing “in” of Na+ ions and rushing “out” of K+ ions that occur during cycles of depolarization and repolarization of an action potential take only a few milliseconds – is something that neurons would have tight control over.

**PODCAST accompanies this post** In the brain, as in other aspects of life, timing is everything. On an intuitive level, its pretty clear, that, since neurons have to work together in widely distributed networks, they have a lot of incentive to talk to each other in a rhythmic, organized way. Think of a choir that sings together vs. a cacophony of kids in a cafeteria – which would you rather have as your brain? A technical way of saying this could be, “Clustered bursting oscillations, with in-phase synchrony within each cluster, have been proposed as a binding mechanism. According to this idea, neurons that encode a particular stimulus feature synchronize in the same cluster.” A less technical way of saying this was first uttered by Carla Shatz who said, “Neurons that fire together wire together” and “Neurons that fire apart wire apart“. So it seems, that the control over neural timing and synchronicity – the rushing “in” of Na+ ions and rushing “out” of K+ ions that occur during cycles of depolarization and repolarization of an action potential take only a few milliseconds – is something that neurons would have tight control over.

With this premise in mind, it is fascinating to ponder some recent findings reported by Huffaker et al. in their research article, “A primate-specific, brain isoform of KCNH2 affects cortical physiology, cognition, neuronal repolarization and risk of schizophrenia” [doi: 10.1038/nm.1962]. Here, the research team has identified a gene, KCNH2, that is both differentially expressed in brains of schizophrenia patients vs. healthy controls and that contains several SNP genetic variants (rs3800779, rs748693, rs1036145) that are associated with multiple different patient populations. Furthermore, the team finds that the risk-associated SNPs are associated with greater expression of an isoform of KCNH2 – a kind of special isoform – one that is expressed in humans and other primates, but not in rodents (they show a frame-shift nucleotide change that renders their ATG start codon out of frame and their copy non-expressed). Last I checked, primates and rodents shared a common ancestor many millenia ago. Very neat – since some have suggested that newer evolutionary innovations might still have some kinks that need to be worked out.

In any case, the research team shows that the 3 SNPs are associated with a variety of brain parameters such as hippocampal volume, hippocampal activity (declarative memory task) and activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). The main suggestion of how these variants in KCNH2 might lead to these brain changes and risk for schizophrenia comes from previous findings that mutations in this gene screw up the efflux of K+ ions during the repolarization phase of an action potential. In the heart (where KCNH2 is also expressed) this has been shown to lead to a form of “long QT syndrome“. Thus, the team explores this idea using primary neuronal cell cultures and confirms that greater expression of the primate isoform leads to non-adaptive, quickly deactivating, faster firing patterns, presumably due to the extra K+ channels.

The authors hint that fast & extended spiking is – in the context of human cognition – is thought to be a good thing since its needed to allow the binding of multiple input streams. However, in this case, the variants seem to have pushed the process to a non-adaptive extreme. Perhaps there is a seed of an interesting evolutionary story here, since the innovation (longer, extended firing in the DLPFC) that allows humans to ponder so many ideas at the same time, may have some legacy non-adaptive genetic variation still floating around in the human lineage. Just a speculative muse – but fun to consider in a blog post.

In any case, the team has substantiated a very plausible mechanism for how the genetic variants may give rise to the disorder. A scientific tour-de-force if there ever was one.

On a personal note, I checked my 23andMe profile and found that while rs3800779 and rs748693 were not assayed, rs1036145 was, and I – boringly – am a middling G/A heterozygote. In this article, the researchers find that the A/As showed smaller right-hippocampal grey matter volume, but the G/A were not different that the G/Gs. During a declarative memory task, the GGs showed little or no change in hippocampal activity while the AA and GA group showed changes – but only in the left hippocampus. In the N-back task (a working memory task), the AA’s showed more changes in brain activation in the right DLPFC compared to the GGs and GAs.

For further edification, here is a video showing the structure of the KCNH2-type K+ channel. Marvel at the tiny pore that allows red K+ ions to leak through during the repolarization phase of an action potential. **PODCAST accompanies this post**

Posted in KCNH2 | Tagged 23andMe, Action potential, Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, Frontal lobe, Gene, Gene expression, Hippocampus, Neuron, schizophrenia, Single-nucleotide polymorphism | Leave a Comment »

- Image via Wikipedia

Just popped into my inbox …

Dear Registrant,

Thank you for participating in TruGenetics’ pre-registration Beta.

We wanted to inform you that despite our best efforts and contrary to our expectations, our funding sources did not come through and to date, we have been unable to secure funding for launching our genome scanning program. Given the current economic climate, we are also unsure how long the funding process will take.

We understand that some of you may want to seek genome scanning services from other companies. Therefore, we are offering you the option to remove your information from our database. Using your username and password, you can log on to http://www.trugenetics.com and delete your record from our database at your convenience.

We will continue our fundraising efforts and we will inform you of any progress toward our goal.

Again, we appreciate you pre-registering with TruGenetics.

Sincerely,

TruGenetics Management Team

Posted in Uncategorized | Leave a Comment »

pointer to next week’s conference in Bethesda NIH State-of-the-Science Conference: Family History and Improving Health. From the website, “Family history is also critical to determining who will benefit from genetic testing for both common and rare conditions, and can facilitate interpretation of genetic test results.” You can watch live or later via an archived webcast!

pointer to next week’s conference in Bethesda NIH State-of-the-Science Conference: Family History and Improving Health. From the website, “Family history is also critical to determining who will benefit from genetic testing for both common and rare conditions, and can facilitate interpretation of genetic test results.” You can watch live or later via an archived webcast!

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Genetic testing, Health care, Personalized medicine | Leave a Comment »

- Image via Wikipedia

Among the various (and few) significant results of recent landmark whole-genome analyses (involving more than 54,000 participants) on schizophrenia (covered here and here), there was really just one consistent result – linkage to the 6p21-22 region containing the immunological MHC loci. While there has been some despair among professional gene hunters, one man’s exasperation can sometimes be a source of great interest and opportunity for others – who – for many years – have suspected that early immunological infection was a key risk factor in the development of the disorder.

Such is the case in the recent paper, “Prenatal immune challenge induces developmental changes in the morphology of pyramidal neurons of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in rats” by Baharnoori et al., [doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.003]. In this paper, the authors point out that Emil Kraepelin, who first described the disorder we now call schizophrenia, had suggested that childhood inflammation of the head might be an important risk factor. Thus, the immunopathological hypothesis has been around since day 0 – a long time coming I suppose.

In their research article, Baharnoori and colleagues have taken this hypothesis and asked, in a straightforward way, what the consequences of an immunological challenge on the developing brain might look like. To evaluate this question, the team used a Sprague-Dawley rat model and injected pregnant females (intraperitoneally on embryonic day 16) with a substance known as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) which is known to mimic an infection and initiate an immune response (in a manner that would normally depend on the MHC loci found on 6p21-22). Once the injections were made, the team was then able to assess the consequences to various aspects of brain and behavior.

In this paper, the team focused their analysis on the development of the frontal cortex and the hippocampus – 2 regions that are known to function poorly in schizophrenia. They used a very, very focused probe of development – namely the overall shape, branching structure and spine formations on pyramidal cells in these regions – via a method known as Golgi-Cox staining. The team presents a series of fantastically detailed images of single pyramidal cells (taken from postnatal day 10, 35 and 60) from animals who’s mothers were immunologically challenged and those who were unexposed to LPS.

Briefly, the team finds that the prenatal exposure to LPS had the effect of reducing the number of dendritic spines (these are the aspects of a neuron that are used to make synaptic connections with other neurons) in the developing offspring. Other aspects of neuronal shape were also affected in the treated animals – basically amounting to a less branchy, less spiny – less connectable – neuron. If that’s not a basis for a cognitive disorder than what else is? Indeed, the authors point out that such spines are targets – in early development – for interneurons that are essential for long-range gamma oscillations that help distant brain regions function together in a coherent manner (something that notably does not happen in schizophrenia).

Thus, there is many a reason (54,000 strong) to want to better understand the neuro-immuno-genetic-developmental mechanisms that can alter neuronal structure. Exciting progress in the face of recent genetic setbacks!

Posted in Frontal cortex, Hippocampus, MHC loci | Tagged Development, Epigenetics, Frontal lobe, schizophrenia | 1 Comment »

- Image via Wikipedia

In the lowly worm Caenorhabdritis elegans, it has been long possible to understand the exact lineage of each of its 959 somatic cells. That is, one can know for each and every cell, who its parental cell was, and grand-parental cell etc., back until the very first cell division (feast your eyes on these movies of C. elegans development). Similarly, it is possible to follow what networks of genes are transcribed (turned on/off) as these cellular divisions and differentiations occur. In this sense, one can reconstruct the transcriptional events occuring within the nucleus of a cell with outward changes in cell structure and migration as the lowly li’l worm develops.

If, for example, there were genes that led to abberant behavior in the worm, then it would be possible to query when and where such a gene was expressed and under who’s transcriptional control. Such a tool would be powerful and useful indeed – especially if there were genetically-based abberant behavioral disorders in worms. Nice to be a lowly worm (psychiatrist) these days.

So, what about human brains? and human genes that have been correlated with changes in brain structure, brain activity and/or brain disorders? Are there tools that allow us to reconstruct an outward cellular lineage and correlate it with a transcriptional lineage? Where might genes for abberant brain function lie in such a lineage? – perhaps early in the course of brain development, with many subsequent genes under its control and whose expression mediates the development of many daughter and granddaugter cells? Or perhaps mental illness risk genes have little regulatory oversight and have rather specific effects on a small number of specialized cells later in the course of development? Wouldn’t we like to know!

With this query in mind, it was fun to read a recent article entitled, “The organization of the transcriptional network in specific neuronal classes” by Winden et al., [free access doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.46]. This article describes an amazing bioinformatic open-public use tool called, “Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis” which seems to have been developed in the lab of Steve Horvath at UCLA (one of the co-authors). The authors examined the gene expression data from an array of 12 different adult neuronal cell types (this analysis was performed using mouse brain tissue) and used the WGCNA method to organize the patterns of gene expression and then asked how they relate to different cell morphologies and physiological attributes (such as firing patterns). In this way, they are beginning to construct a genetic road map of mammalian brain development that is much like that for C. elegans.

To me, the really exciting thing about this particular analysis (they also have used this method to compare gene expression in a brain-region-specific way in humans vs. chimpanzees) is that the different cell types in the brain perform different – here comes the punchline – computations! Thus, if there be a genetic code for neuron structure/function (and from the work of Horvath and colleagues, it looks like there be), then it should be possible to begin to assign these module-specific genetic factors to computations or computational properties of the brain – and have a more mechanistic synthesis of genetic influences on cognition.

A few examples from the paper include different transcriptional co-expression networks (modules) for glutamateric and GABAergic cell types, which have distinct functions in the regulation of neural dynamics (ie. computation). Further analysis yielded different co-expression modules for the development of different types of interneurons. The team also finds different co-expression modules for aspects of cell-firing and synaptic structure which would very likely have effects on neural-network dynamics. Also, there is an analysis of the RGS4 knockout mouse and a query into the specificity of the co-expression module that contains RGS4 (very few abberant gene expression changes outside the RGS4 module) which – since RGS4 has been associated with schizophrenia – reveals clues on the expected consequences of RGS4 mutations in humans.

There is really too much to cover in a single blog post, so am going to dig in to the data in more detail and report back later. An amazing tool graciously shared with the community!

Posted in RGS4 | Tagged Development, Gene expression | Leave a Comment »

Interview with Professor Michael Frank: Computational Neuroscience (and Genetics) of Decision Making

If you’re interested in the neurobiology of learning and decision making, then you might be interested in this brief interview with Professor Michael Frank who runs the Laboratory of Neural Computation and Cognition at Brown University.

If you’re interested in the neurobiology of learning and decision making, then you might be interested in this brief interview with Professor Michael Frank who runs the Laboratory of Neural Computation and Cognition at Brown University.

From his lab’s website: “Our research combines computational modeling and experimental work to understand the neural mechanisms underlying reinforcement learning, decision making and working memory. We develop biologically-based neural models that simulate systems-level interactions between multiple brain areas (primarily basal ganglia and frontal cortex and their modulation by dopamine). We test theoretical predictions of the models using various neuropsychological, pharmacological, genetic, and neuroimaging techniques.”

In this interview, Dr. Frank provides some overviews on how genetics fits into this research program and the genetic results in his recent research article “Prefrontal and striatal dopaminergic genes predict individual differences in exploration and exploitation”. Lastly, some lighthearted, informal thoughts on the wider implications and future uses of genetic information in decision making.

To my mind, there is no one else in the literature who so seamlessly and elegantly interrelates genetics with the modern tools of cognitive science and computational neurobiology. His work really allows one to cast genetic variation in terms of its influence on neural computation – which is the ultimate way of understanding how the brain works. It was a treat to host this interview!

Click here for the podcast and here, here, here for previous blog posts on Dr. Frank’s work.

Posted in COMT, DARPP32, DRD2, Uncategorized | Tagged Artificial Intelligence, Basal Ganglia, Brown University, Cognition, Cognitive science, Dopamine, economics, interviews, podcasts, Working memory | Leave a Comment »

- Image via Wikipedia

Within the genetic news flow, there is often, and rightly so, much celebration when a gene for a disease is identified. This is indeed an important first step, but often, the slogging from that point to a treatment – and the many small breakthroughs along the way – can go unnoticed. One reason why these 2nd (3rd, 4th, 5th …) steps are so difficult, is that in some cases, folks who carry “the gene” variant for a particular disorder, do not, in fact, display symptoms of the disorder.

Huh? One can carry the risk variant – or many risk variants – and not show any signs of illness? Yes, this is an example of what geneticists refer to as variable penetrance, or the notion of carrying a mutation, but not outwardly displaying the mutant phenotype. This, is one of the main reasons why genes are not deterministic, but much more probablistic in their influence of human development.

Of course, in the brain, such complexities exist, perhaps even moreso. For example, take the neurological condition known as dystonia, a movement disorder that, according to the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation, “causes the muscles to contract and spasm involuntarily. The neurological mechanism that makes muscles relax when they are not in use does not function properly. Opposing muscles often contract simultaneously as if they are “competing” for control of a body part. The involuntary muscle contractions force the body into repetitive and often twisting movements as well as awkward, irregular postures.” Presently there are more than a dozen genes and/or chromosomal loci that are associated with dystonia – two of the major genes, DYT1 and DYT6 – having been identified as factors in early onset forms of dystonia. Now as we enter the era of personal genomes, an individual can assess their (own, child’s, preimplantion embryo’s!) genetic risk for such rare genetic variants – whose effects may not be visible until age 12 or older. In the case of DYT1, this rare mutation (a GAG deletion at position 946 which causes a loss of a glutamate residue in the torsin A protein) gives rise to dystonia in about 30-40% of carriers. So, how might these genes work and why do some individuals develop dystonia and others do not? Indeed, these are the complexities that await in the great expanse between gene identification and treatment.

An inspection of the molecular aspects of torsin A (DYT1) show that it is a member of the AAA family of adenosine triphosphatases and is related to the Clp protease/heat shock family of genes that help to properly fold poly-peptide chains as they are secreted from the endoplasmic reticulum of the cell – a sort-of handyman, general purpose gene (expressed in almost every tissue in the body) that sits on an assembly line and hammers away to help make sure that proteins have the right shape as they come off their assembly lines. Not much of a clue for dystonia – hmm. Similarly, the THAP domain containing, apoptosis associated protein 1 (THAP1) gene (a.k.a. DYT6) is also expressed widely in the body and seems to function as a DNA binding protein that regulates aspects of cell cycle progression and apoptosis. Also not much an obvious clue to dystonia – hmm, hmm. Perhaps you can now see why the identification of “the gene” – something worth celebrating – can just leave you aghast at how much more you don’t know.

That these genes influence an early developmental form of the disorder suggests a possible developmental role for these rather generic cogs in the cellular machinery. But where? how? & why an effect in some folks and not others? To these questions, comes an amazing analysis of DYT1 and DYT6 carriers in the article entitled, “Cerebellothalamocortical Connectivity Regulates Penetrance in Dystonia” by Argyelan and colleagues [doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2300-09.2009]. In this article, the research team uses a method called diffusion tensor imaging (sensitive to white matter density) to examine brain structure and function among individuals who carry the mutations but either DO or DO NOT manifest the symptoms. By looking at white matter tracts (super highways of neural traffic) throughout the brain the team was able to ask whether some tracts were different in the 2 groups (as well as a group of unaffectd, non-carriers). In this way, the team can begin to better understand the causal pathway between these run-of-the-mill genes (torsin A and thap1) and the complex pattern of muscle spasms that arise from their mutations.

To get right to the findings, the team has discovered that in one particular tract, a superhighway known as “cerebellar outflow pathway in the white matter of lobule VI, adjacent to the dentate nucleus” (not as quaint as Route 66) that those participants that DO manifest dystonia had less tract integrity and connectivity there compared to those that DO NOT manifest and healthy controls (who have the most connectivity there). Subsequent measures of resting-state blood flow confirmed that the disruptions in white matter tracts were correlated with cerebellar outflow to the thalamus and – more importantly – with activity in areas of the motor cortex. The correlations were such that individuals who DO manifest dystonia had greater activity in the motor cortex (this is what dystonia really comes down to — too much activity in the motor cortex).

Thus the team were able to query gene carriers using their imaging methods and zero-in on “where in the brain” these generic proteins exert a detrimental effect. This seems to me, to be a huge step forward in understanding how a run-of-the-mill gene can alter brain function in such a profound way. Now that they’ve found the likely circuit (is it the white matter per se or the neurons?), more focus can be applied to how this circuit develops – and can be repaired.

Posted in Cerebellum, Motor cortex, Thalamus, Thap1, Torsin A | Tagged Biology, Development, Diffusion MRI, Disease, DNA, Dystonia, Gene, Genetics, Mental disorder, Mutation, White matter | Leave a Comment »

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)